Church of Santa Maria del Popolo – a treasury of art and a mausoleum of family pride

Another reason tourists come to the basilica is the Chigi Chapel, famous not so much for the great works of Renaissance and Baroque found within, but due to Dan Brown, since it is here that he placed one of the emotional scenes of his oft-read book, which had in addition been made into a movie.

However, for those who come here, not paying attention to fashion or bestsellers, the church has a lot to offer. It is a veritable treasury of art, where for hours one can wander using eyes or the imagination, between one sculpture and another, muse over the fate of man and its fleetingness, while looking on at the incredible funerary monuments, then again marvel at almost delicate, somewhat naïve beauty of early-Renaissance frescoes. All of this was gathered here, with a single goal in mind, to immortalize two Roman families – the della Rovere and Chigi. But let us start from the beginning.

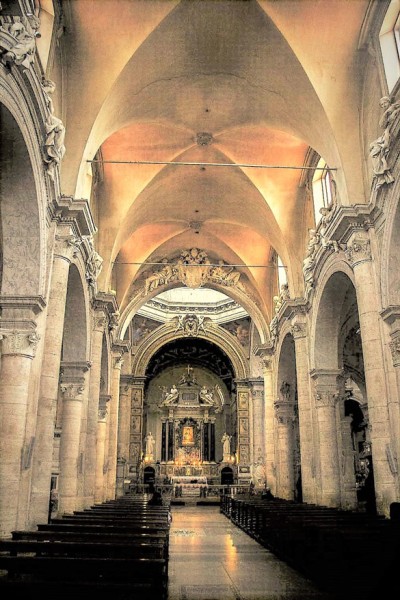

The church is a Renaissance basilica situated directly next to the Porta del Popolo city gate. It has a very modest, almost inconspicuous façade. A legend says, that a walnut tree stood here, inside which the condemned soul of Emperor Nero resided – since the tree was situated in the location of his ancient tomb. This soul haunted visitors who came into the city. When news of this reached the ears of Pope Paschal II, he ordered prayers, which however proved of little use. Only when the Virgin Mary appeared to him in a dream, and commanded him to cut down the tree and build a church, a miracle occurred. Thus, a modest chapel was built, reportedly funded by donations coming from the Roman populace (hence the dedication of the church: Our Blessed Lady of the People). At the same time, the church was to be an expression of gratitude for the fruits yielded by the First Crusade to the Holy Land and the conquest of Jerusalem (1099). On the other hand, Pope Gregory IX, in thanks for an end to the plague which ravaged the city in 1231, expanded the church and placed the Franciscan friars within.

However, the basilica owes its present-day appearance to Pope Sixtus IV from the della Rovere family, one of the greatest patrons of art in the history of the papacy and at the same time a great schemer, a man of rather miserable reputation, thanks to whom the papacy’s image had suffered greatly. As soon as he ascended to St. Peter’s throne in 1472, he ordered the previous structure to be torn down and replaced with a modern, Renaissance body while at the same time ordering a monastery to be erected destined for Augustinians, who were brought in to replace the Franciscans. It was the intention of the pope to create a new image of the city, at the important for pilgrims and visitors location – the Porta Flaminia (present-day Porta del Popolo), as well as to ensure a representative location for his own burial and for that of his family. For this reason he brought first and second-rate artists from the birthplace of Renaissance, Florence – painters, sculptors and stucco artists. Rome shone with a previously unknown brightness. It should therefore come as no surprise, that the church became a very fashionable and prestigious structure: the richest and the most important, or at least those who thought of themselves as such desired to be buried within its walls. And it was not only those connected with the della Rovere family but also its enemies and competitors. Thanks to donations and funds given on behalf of the monastery and the church it was possible to ensure oneself with the most convenient location for a funerary monument or even a chapel, of course the closer to the main altar, the better. The perspective of being buried next to the pope was also not without significance, especially for those who hoped for his support in the afterlife.

The wealthiest families could allow for painting decorations of their chapels, and those which were most often admired were created by none other than Pinturicchio – the decorator of papal apartments, whose paintings are found in four chapels out of all located here. Most of these have kept their decorations, however, some of them fell victim to latter decorations.

A gift from the aforementioned Pope Gregory IX, was also a miraculous icon of Our Lady, which, as legend would have it, had been painted by St. Luke himself, and previously located in the Sancta Sanctorum Chapel on the Lateran. Today it adorns the main altar of the basilica. It is most likely the work of the master of the then monastery and the Church of San Saba and comes from the XIII century. Initially the apse was adorned by another, exquisite, Renaissance, marble altar, completed by Andrea Bregno, which was created in 1478, at the initiative of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, the latter Pope Alexander VI. During the XVII century modernization, the altar was taken apart and today it can be viewed in two parts – one is found in the church sacristy, the other in the first chapel from the enterance (Cappella Montemirabile).

The current altar – which seems to be too large and too monumental – was created in 1627. It covered up the outstandingly designed by Donato Bramante at the beginning of the XVI century presbytery, of which the greatest decorations were the stained-glass windows, allowing light into the interior (1509), but also two, multi-story tombstones located by the wall. Both the enlargement of the presbytery as well as the foundation of the tombstones were the initiative of another pope from the della Rovere family – Julius II. In order to accomplish this, the ambitious and generous founder brought the great Florentine, sculptor Andrea Sansovino to Rome, who between the years 1505 and 1509 created, in the city on the Tiber, the first Renaissance tombstones depicting not dead but sleeping figures, captured in a triple arcade of a triumphant arch and decorated with statues of the virtues and candelabra reliefs. Unfortunately, today barely visible, they present two important for the pope cardinals, to whom he was not only related, but belonged to the same political faction. And even if there were animosities among them, all of them were bound by their vehement dislike of the previous pope, Alexander VI as well as a will to drive the French out of Italy. The first tombstone depicts the nephew of Pope Sixtus IV and an influential nepot, as well as a cousin of Pope Julius II – Cardinal Girolamo Basso della Rovere. The second was designated for a true man of the world – Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, a representative of the Sforza family which ruled in Milan, with whom Julius II maintained a difficult and marked with numerous disappointments friendship. Regardless of the interesting political background, both tombstones constitute one of the most important artistic works of the Renaissance and that is why it is worth taking a closer look at them (see: Tombstones of Girolamo Basso della Rovere and Ascanio Sforza).

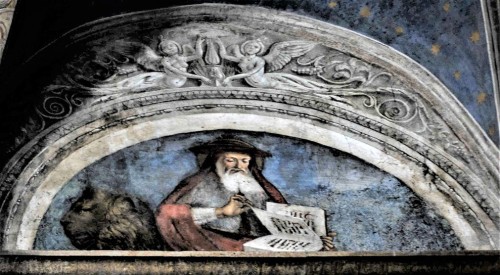

On the ceiling of the presbytery, Pinturicchio placed his excellent frescoes in fields decorated with framings (1508-1512): in the middle we see Coronation of Our Lady, while around her sibyls (in round fields), the images of the four Evangelists (in trapezoidal fields), as well as images of the Four Fathers of the Church (in the arcade niches).

The church interior is divided into three naves, opening up onto the side chapels, which are supplemented by a crosswise transept and crowned with a presbytery. The whole is topped off with a multi-sided dome which lets light in. In the XVI century the raw church interior was filled with tombstones and altars, however in the following century it was forgotten and neglected. Finally, it caught the interest of Cardinal Fabio Chigi (the latter Pope Alexander VII), when he recalled his famous ancestor and decided to bestow a new, almost modern look upon his chapel. And along with it the whole church.

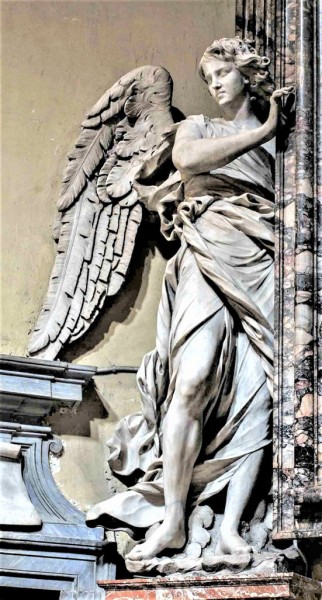

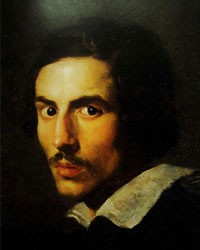

In 1652 he commissioned the famous Gian Lorenzo Bernini to modernize the church. It was to be enlarged with chapels by the altar (left and right transept). The aim was to bring back the basilica’s former prestige, especially due to the fact that it housed the Chigi family chapel. It was then, that those who sought a worthy place of burial once again became interested in the building. Thanks to their financing new chapels were created and old ones were reconstructed, some statues were removed, others transferred to the corridor leading into the sacristy, or to the sacristy itself. The nave interior with a cross vault was also given a new, Baroque look. For this purpose, pairs of saintly women and angels made in stucco, were placed upon the cornice, and they are still situated there today. Some of these hold the papal emblem with the Chigi della Rovere coat of arms (six mountains, a star and an oak tree). It was designed by Bernini, and completed by his ever-present students and collaborators, excellent stucco artists of the Baroque period, including Antonio Raggi, Giovanni Francesco de Rossi and Ercole Ferrata.

Prior to the church becoming a mecca for the admirers of the talent of Caravaggio, the places that drew the most attention were two chapels, created by the most outstanding artists of two periods – Renaissance and Baroque. And it is those very chapels, where we shall begin our journey through the greatest artistic works found inside the church.

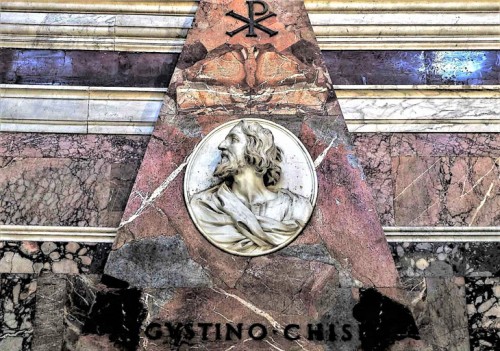

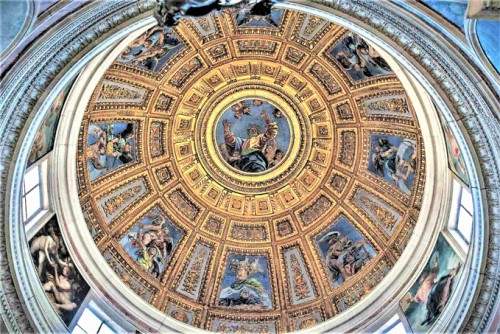

- Cappella Chigi (second on the left) it was created in 1516 for the papal banker and patron of the arts, but also the richest man in Rome, Agostino Chigi. The creator of the concept of the chapel was Raphael, who had earlier got himself into the good graces of the family with his exceptional decoration of their suburban residence – villa Farnesina. The posthumous residence of the banker, was to amaze just as the paintings of his villa had. The chapels were laid out with marbles, decorated with pilasters, while the tombs of Agostino and Sigismondo were given the forms of ancient pyramids. It is assumed, that the inspiration for these unusual at that time forms was two twin pyramids – remains of ancient tombstones, excavated at that time on a nearby square. In the windows of the chapel there are frescoes of a Florentine, mannerist Francesco Salviati, depicting scenes from the Genesis. On the other hand, in the altar, there is a painting on a stone, depicting the Nativity of the Virgin (1526), painted by the Venetian artist, Sebastiano del Piombo. The dome at the top of the chapel is embellished with mosaics, once again completed according to the cantons of the great, considered by his contemporaries as unmatched master of his craft – Raphael, who died while working on the chapel in 1520. Their principal topic is the Creator of the Firmament, shown in the company of the allegoric figures of the Sun and the six planets which were known at that time.

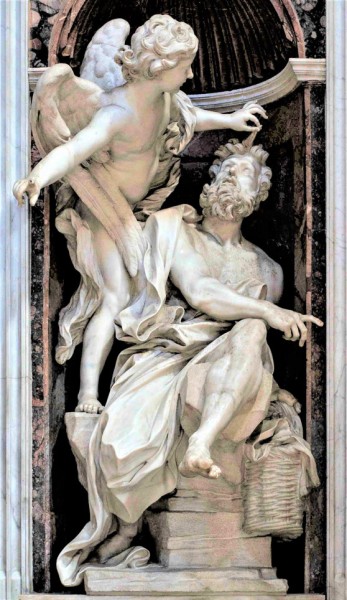

The sculpture decorations of the chapel are made up of statues of Old Testament prophets. Two of them – Jonah and Elijah – were completed by Raphael’s student, Lorenzetto, while two remaining ones (Habakkuk and Daniel), were completed over one hundered years later and were the work of Gian Lorenzo Bernini. These last ones were of course created at the commission of the aforementioned Fabio Chigi, who assumed the throne of St. Peter nearly 140 years after the construction of the chapel. He ordered Bernini to modernize the chapel in a new Baroque spirit and to supplement the missing sculptures while also creating marble reliefs to decorate the pyramids. Bernini was also the author of the design of the marble floor mosaic showing Death carrying the Chigi della Rovere coat of arms, accompanied by the inscription Mors ad Caelos (Death to Heaven). The theme which inspired the artists in creating the iconography of place was death, resurrection and salvation. That is the reason for selecting specific prophets immortalized in marble and visible in the chapel niches. Each of them carries a different message, but together they speak of conquering death by faith. From the artistic point of view it is also interesting to compare the Renaissance figures (by Lorenzetti) with the Baroque ones (Bernini). In an exceptional way, this comparison shows, how harmony, striving for balance and classical beauty of the Renaissance were put in opposition to the movement, dynamics and expressionism of Baroque – Bernini’s figures seem to almost burst out of the niches in which they are found.

Near this chapel, an imposing Rococo creation, destined for Maria Odescalchi Chigi (1771), was built into the church pillar, A roaring lion at the base of this pillar, a banner on a rock, on which the name of the deceased was immortalized, all this reminds us of the fashion which came to be in the XVIII century, for theatrically draped tombstones. Elements used in its decorations refer to heraldic symbols of families, from which the twenty-year old young woman came, dying in labor after the birth of her third child – the lion (Odescalchi), the mountain (Chigi) and a smoking incense burner.

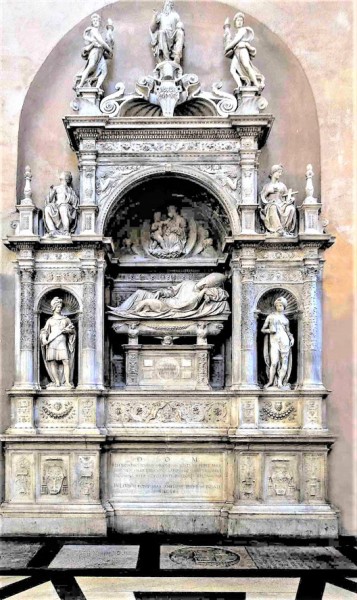

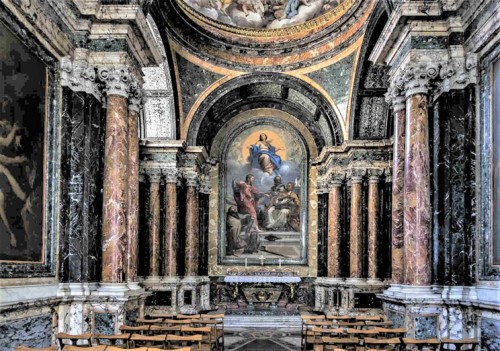

- On the opposite side of the church, directly ahead, there is an equally interesting chapel – Cybo Chapel, founded for the Cybo family. And it could also claim to have given Rome one of its bishops – Innocent VIII, who will be remembered in history as the first pope who officially legalized his children. The chapel was purchased by his nephew, Cardinal Lorenzo Cybo de Mari, who ordered it to be decorated with frescoes by Pinturicchio (1489-1503) and furnished with tombstone sculptures from the workshop of Andrea Bregno. Yet it seems that, for subsequent members of the family the chapel was not representative and prestigious enough, since nearly 150 years later, another founder – Cardinal Alderano Cybo, the secretary of Pope Innocent X, shocked viewers with the splendor of the decorations used within – only they could appropriately commemorate the cardinal’s family. In their creation, Renaissance frescoes were destroyed, while new arrangements of the chapel were entrusted to a student of Bernini, Carlo Fontana, who used ascending columns, pilasters and balustrades, made of valuable marble, dark-green serpentine and bronze jasper in their decoration. The main altar contains a painting representing a discussion on the topic of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary which at the time occupied the minds of church dignitaries; the debate is participated in by St. John the Evangelist as well as the Fathers of the Church: St. Gregory the Great, St. John Chrysostom and St. Augustine. The painting was created in 1689 and was painted by the principal representative of late Baroque, Carlo Maratti. All this splendor was arranged to commemorate those buried in the chapel, Cardinal Alderano Cybo (1683) and Lorenzo Cybo (1684), whose funerary monuments were completed by the valued at that time author of numerous Roman sculptures, Francesco Cavallini. In this way one of the most representative works of the funerary art of the Baroque period, was created.

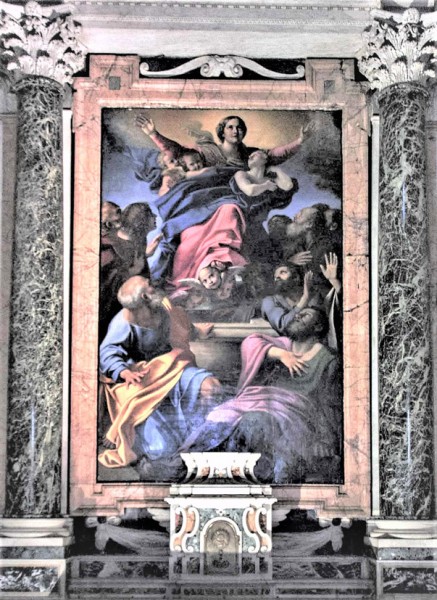

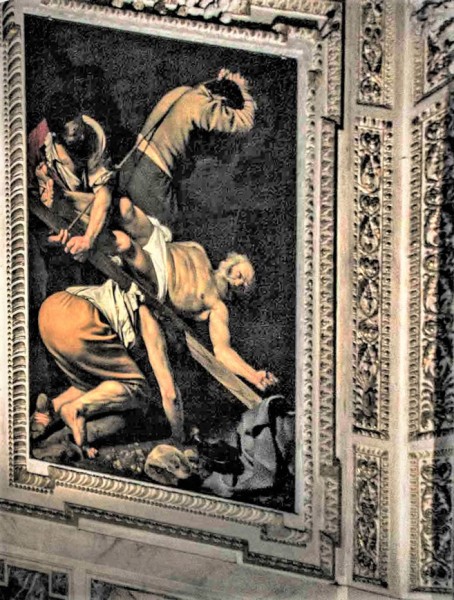

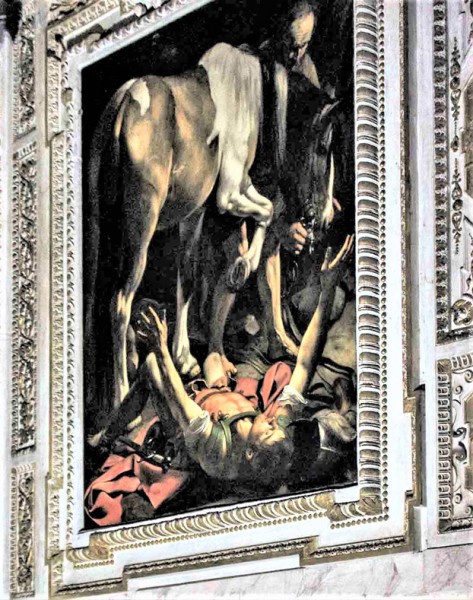

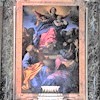

- Next comes the most sought-after funerary chapel in the church, meaning the Cerasi family chapel. Work on it was entrusted to two painters - Annibale Carracci, who was tasked with painting main altar, and Caravaggio, who was asked to complete the side paintings. Caravaggio's canvas were devoted to the two greatest martyrs of the Church and the patrons of Rome - St. Peter, the one who was supposed to be like the rock on which the Church was built, and St. Paul, an erudite and a convert. On the other hand, Carracci’s depicts a theme often present in a post-Trent iconography - the miraculous Assumption of the Virgin Mary. Looking at this colorful composition, which seemed model at that time, while its author was considered one of the most talented painters of his time, we can better understand the kind of a breakthrough that Caravaggio made in painting. Work on the paintings did not progress as quickly as he would have wanted. Once again he turned to alcohol, wandered the streets with his friends, and got into brawls. Nevertheless, in 1601, after several attempts, he managed to satisfy the wishes of his clients and two excellent canvases were placed in the chapel - Conversion of St. Paul and the Crucifixion of St. Peter.

Apart from the aforementioned chapels, paintings and funerary statues, other works in the church also merit attention, those which adorn the chapels of families, who desired to leave something behind, also in the artistic dimension:

- Cappella della Rovere (first on the right), of course belonging to the family, which could boast the aforementioned Pope Sixtus IV. He himself was ultimately buried in St. Peter’s Basilica (San Pietro in Vaticano). However, in this chapel, his nephews, Domenico and Cristoforo founded their tombstones. These are the works of Andrea Bregno (1501) and the Florentine artist, Mino da Fiesole. On the opposite side is the tombstone of another family member, Cardinal Giovanni de Castro, transported here from another location, and seemingly too large for this interior. However, it is not they that draw the onlooker’s attention, but rather the outstanding altarpiece by Pinturicchio – Nativity. It constitutes part of a decoration, which the painter and his workshop completed between the years 1488 and 1490 and which were devoted to the life of the patron of the chapel – St. Jerome. We will be able to see him in the preserved lunettes of the vault.

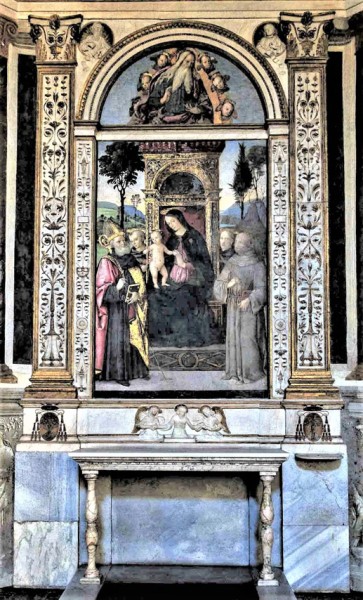

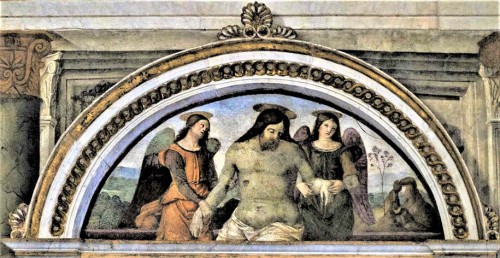

- In the Basso della Rovere Chapel (third on the right), founded by Cardinal Girolamo delle Rovere, his own tombstone is located. Once again it is worth mentioning frescoes completed by Pinturicchio and his workshop depicting Our Lady with Saints in the main altar, as well as scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary in the lunettes and on the walls. The most beautiful of these, seems to be the scene of the Pieta, placed in the lunette above the tombstone. Visitors to the church are also attracted by unusual black and white paintings found in the lower part of the chapel, the so-called, grisaille, which are supposed to imitate reliefs. They show scenes of the martyrdom of saints Peter, Paul and Catherine of Alexandria.

- Cappella Costa (fourth on the right) does not emanate with spectacular works of art and known artists, however it is interesting since it has been preserved in an unaltered form since its creation, thanks to which it constitutes an excellent example of Renaissance decoration. Initially it also belonged to the della Rovere family, however it ultimately came into the possession of a Portuguese cardinal – Jorge da Costa (on the left). The chapel is dedicated to St. Catherine of Alexandria, and she is the one who occupies the principal spot in the marble altar among St. Lawrence and St. Anthony of Padua. In the lunettes adorning the chapel there are frescoes by Pinturicchio depicting the four Fathers of the Church.

- Cappella Mellini (third on the left) – while it was created in the XV century, in the XVII century it was thoroughly reconstructed and altered. The most interesting objects within are the busts of two cardinals from the Mellini family. One of them commemorates Giovanni Garzia Mellini and is the work of a significant Baroque sculptor Alessandro Algardi, who was a competitor of the great Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

- Cappella Montemirabile – baptismal chapel (first on the left), initially dedicated to St. John the Baptist, while in the middle of the XVI century it became a baptismal chapel. In XVII century it was thoroughly modernized – the ciboria on both sides of the altar were mounted, which are used for storing holy water and oil. The relief slabs, initially found in the main altar of the church, completed by Andrea Bregno are supplemented by a decoration made up of grotesque and candelabra ornaments.

- Cappella Santa Rita da Cascia or Cappella Cicala (in the transept, second on the right). Today it looks like a typical XVII century chapel and from the artistic point of view it contains nothing of significance. However, despite of that fact it is still interesting. It speaks of the times, when it was common for popes to have not only lovers but children as well, and this did not cause any great commotion, while the way bishops of Rome lived was more similar to the lives of the then unrestrained wealthy class than shepherds of the Church. The chapel which was created here at the end of the XV century, was officially founded by Giorgio della Croce, the second husband of Vanozza Cattanei, known in all of Rome as the partner and mother of four children of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, the latter Pope Alexander VI. The pope most likely supported his concubine in her efforts to possess her own chapel in this renowned church, even when he already had a much younger, only fifteen-year-old successor. This was due to the fact that it was not only destined to be the final resting place of Vanozza, but as it turned the papal son – Juan, most likely killed by his own brother Cesare Borgia and cast into the Tiber. Another of Vanozza’s sons buried within the chapel walls was Ottavio (from her marriage with della Croce). A gesture of both love and respect for this woman was a painting found inside the chapel at that time of St. Lucy of Syracuse, who was particularly venerated by the Borgia family, and who here possessed the facial features reminiscent of Vanozza. She was surrounded by a group of donors, among them the pope and his children. We can only imagine what thoughts entered the head of the Augustinian, Martin Luther, who came to Rome at that time, and was a guest in the nearby monastery, and even if he did pray in the Borgia-Cattanei Chapel in front of the painting of St. Lucy, he had to have seen the secularization of traditions, which he certainly could not comprehend. As we know, when he came to his senses, the Roman Catholic Church shook in its foundations – out of an inconspicuous reform movement, the Reformation was born. When in the XVII century works to modernize the basilica were started, Pope Alexander VII, fully aware of the utter defeat suffered by the Church in the struggle with Luther, ordered the altar to be removed from the chapel. Even earlier Vanozza’s tombstone was removed (today it is located in the vestibule of the Church of San Marco), while the only souvenir of the righteous at the end of her life matron, who lived until the age of 76 and was a devoted parishioner and generous founder, is the marble bowl for holy water which she had commissioned (presently in the sacristy), adorned with the Borgia coat of arms – easily recognizable, since a bull is found in one of the four fields.

In the sacristy (we can ask to enter, on the right side of the transept) we can see the central part of the aforementioned altar of cardinal Borgia, or more appropriately the altar tabernacle sculpted by Andrea Bregno (1478).

Leaving the church, there are two more tombstones that certainly merit our attention. One of these, created at the start of the XVIII century, in a truly spectacular way commemorates the Duchess Maria Eleonora from the noteworthy Boncompagni family. It has just about everything – the dragon referencing the family coat of arms seems to be alive, the skeleton skull at the top truly inspires fear, while all of it is supplemented by tibias drawn together by ribbons and other mysterious allegories.

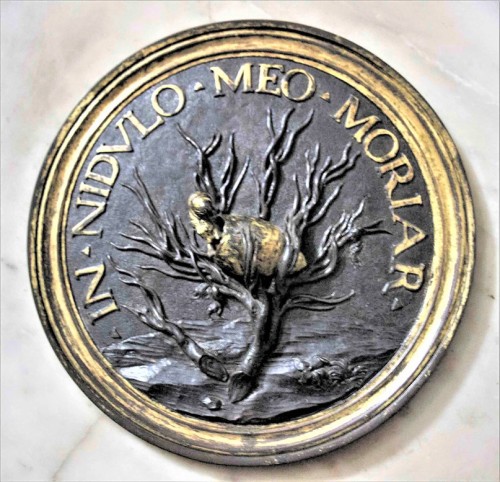

The second tombstone seems to be rather macabre but in truth in brings consolation. It is found right at the enterance (on the left) and it is easily overlooked. It is dedicated to an architect by the name of Gian Battista Gisleni, who while he was born and died (1672) in Rome, spent 38 years of his life in Poland, where he worked as an architect, creator of small architecture, but also occasional funerary decorations for Polish kings and the House of Vasa, as well as the clergy. It seems that his great wish was to be buried in Rome, where he returned six years prior to his death. It took him that much time to plan and complete his funerary monument. It is not bereft of humor and is a typical late-Baroque memento mori – a monument of charades, which hides a message of the fleetingness of human life – understood as a temporary state an overture to resurrection. At the top is the artist’s portrait, in his earthly guise, and it is accompanied by an inscription which reads: NEQUE HIC VIVUS (neither living here). The ending to this sentence is visible at the bottom, by a skeleton placed behind the grate, dressed in a white shroud: NEQUE ILLIC MORTUS (nor dead there). In the center there are two bronze medallions: one depicts a caterpillar with an inscription: IN NIDULO MEO MORIAR (I my nest I shall die), the second a phoenix – the immortal birth rising out of the ashes with the words: UT PHOENIX MULTIPLICABO DIES (as a phoenix I shall multiply my days). And with this message, we can depart from this wondrous church – a veritable arena of human ambitions but also a vestibule of eternal life.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !